Ranking and Missing Doornails

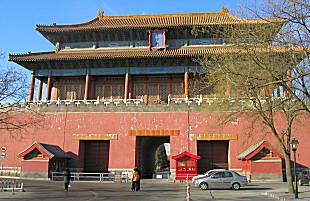

Donghuamen was the primary gate for food and goods delivery to the Palace City. The above picture shows the gate in 1900 and with a contemporary rollover picture

In the 1900s deliveries were still made by donkey cart as is clearly seen. The picture was obviously taken during the waning Qing dynasty since the squatting driver (arrow) has a queue.

The street in front of the gate was heavily used as a commercial area, which is clear from above picture. This is even the case today: If you look up Donghuamen on the web you'll se that most hits will center around the street in front being famous for its many restaurants.

Architectualy the gate is identical to its northern and western sisters, Shenwumen and Xihuamen.

The gate has three doorways -a larger one in the center and two smaller ones on each side. The doorways are arched, but made rectangular or square on the facing away from the Palace city.

The gate tower has five bays and a double eave "xieshan" roof covered with yellow glazed tiles. A white balustrade adorns the perimeter of the top of the platform.

The dismounting stone platforms and steles on both sides of the gate have long since been removed. They served as reminder to visitors to alight their horses or palaquins before entering the gate.

Ranking was almost an obsession for the Ming (1368-1644) as well as the subsequent Qing (1644-1911). This was extended into almost any imaginable group of society: Solidiers, eunuchs, waiters, craftsmen, concubines, palace maidens, entertainers, prostitutes, banners, servants, tailors, and so on.

As an example of how far this was taken, during the Qing the palace concubines were ranked on a scale of no less than eight grades: Starting from the top was the empress, imperial honorable consort, honorable consort, consort, consort-in-ordinary, honorable lady, lady-in-waiting and, at the bottom of the heap, responder.

Bureaucracy went so far as to officially regulate the number of concubines in each of the top five groups as well as the color of their eating and drinking vessels and tools between the groups. Plates with green dragon motifs on a yellow background was prestigious and reserved for the exclusive use by honerable consorts, rank 2 and 3.

Ranking was also applied to common services like restaurants, hotels, hostels, theaters, not unlike what is done today.

In the Ming and the Qing it went so far as to ranking buildings, gates and roads.

Anyone who has visited a former imperial Chinese building will be familiar with the little figurines adorning the four corners of the Xieshan roofs. These pages will have a section dedicated to explaining the purpose of each of these figurines, but suffice it to say here that one could easily identify the importance of a gate by simply counting the number of figurines at the corners.

In the Palace City there was a clear connection between somebody's rank and the gates through which he would be allowed to pass, simply by associating his rank with the number of figurines on the gate roof corners. Simple and effective, but highly bureaucratic.

In terms of figurines at the corners and not counting the man on the hen in front, Donghuamen, Xihuamen and Wumen each had seven, whereas Wumen could boast nine -most likely because this was the designated gate to be used by the emperor.

The four gates of the Palace City were even ranked according to political importance. Wumen was obviously the highest, being the only gate through which visiting dignitaries, envoys, vassals, generals, officials, etc. could enter. Next in line was Shenwumen in the north, since this was to be used by the imperial family, chief eunuchs, guards, artisans and so on. Third in line was Xihuamen occasionally even being used by the imperial family. The lowest ranking gate politically was by far Donghuamen.

It is no small wonder that the gate renders a sad impression of dilapidation on the above picture from 1900. The Ming dynasty itself was waning and few officials cared to revamp the area in front of a gate that they rarely used. Even their own gate at home undoubtedly looked better than this.

On both sides of Donghuamen and Xihuamen are dismounting steles

Inscriptions in Manchurian, Chinese, Mongolian, Arabic and Tibetan

script tell visitors to dismount at this point

The low ranking of Donghuamen may also go a long way to explain why trade particularly was blossoming outside this gate, since tradesmen in dynastic times were considered inferior, if not outright despicable.

This might also explain why most supplies to the Palace City passed through Donghuamen.

Stigmatization of Donghuamen can also be linked to death -and even to missing nails (sic!).

The deceased emperor and empress would always be carried out from the Palace City through Donghuamen for their funeral and hence people in general would shy away from using this gate as much as possible because of its association with death.

This brings us to another interesting observation and fact, namely that the doors of Donghuamen was the only ones, which only had 72 (nine rows of eight) doornails instead of the 81 (9 rows of 9) of its sister gates.

The reason lies in symbolism - the complementary "yin and yang". Yang (alive) is associated with "single" whereas Yin (dead) is associated with "double". It follows that the total number of nails on a door, through which the deceased would be carried, could not end on the digit 1 and hence one row was deliberately left out so that the total number of doornails would end on the digit 2.

Spies are us! Donghuamen has another interesting usage tidbit associated with it. Back in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), imperial spies were allowed to pass unhindered through Donghuamen and were banned from the other three gates.

How to Find it Today?

Start in front of Wumen and follow the road right (east) alongside the moat. Pass the SE corner tower and proceed another 150m north and you will find yourself in front of Donghuamen.

The Imperial Guards

in the beginning of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) the honor of guarding the emperor and the palace city was bestowed upon the white, yellow and bordered yellow banners. In the first half of the 1700s the selection was widened.

Some Han Chinese, who had passed the imperial military exams with honor, could also joined the imperial guard force

Also the guard brigade was heavily divided into many ranks. Highest of all were those who guarded the entrance to the Inner Court, Gate of Heavenly Purity or xxxxxmen, the residence of the emperor and his family. The guards manned this gate was manned at all times

Gate of Heavenly Purity in snow (rare)

Occasionally, the emperor would conduct meetings and morning audiences in front of this gate with his senior advisors and ministers.

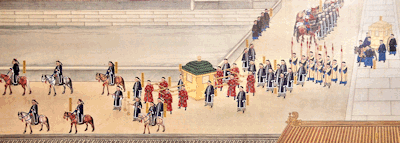

The different ranks of the guards carried different robes so as to easy identify their roles. Consider the different robes in the procession painting left in the main body text on this page.

In the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) imperial guardsmen of the first, second and third rank had a right to wear a peacock feather with one eye in their hats. The emperor could honor a guardsman by allowing him to wear a peacock feather with two eyes and even with three eyes, although that was seldom.

Peacock feather with two eyes

The perifery of the palace city was guarded by elite cavalrymen and imperial soldiers. During a brief period around 1723, these troops were replaced by bannermen.

In the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) forty patrolrooms were set up around the periphery of the palace city. Each room had 10 guards, who patrolled the area throughout the night.

Separate patrols ensured safety in the outer court. Other patrols in the inner court based upon a system of passing red truncheons to each other had a total of 12 designated stops.